This article was authored by Sarayu Agarwal, Program and Co-Creation Manager for Local Impact.

Kutman is a 21-year-old youth born and raised in Myrza Ake village in southern Kyrgyz Republic. He lives with his grandparents as his parents are separated and his mother is working in Russia to make ends meet. He supports his grandparents with the household, mainly looking after livestock.

He is one of the few youth in his village to have completed both secondary and higher education and is yet struggling to find a job.

He shares, “I studied Customs in Uzgen university, but I didn’t find the course very interesting. I need to know someone in the government or save some money before I can land myself a job in this field. My plan is to go to Russia, because I can find more opportunities, and the pay is much better than here.”

Unfortunately, the struggle to find meaningful work and learning opportunities is a shared reality for 1.6 million Kyrgyz youth. The proportion of young people not in employment, education, or training (the youth NEET rate) has remained stubbornly high over the past 11 years and stands at 22% of total youth population in Kyrgyz Republic.

Educational and occupational exclusion of youth is linked to a range of social and economic consequences such as civic disengagement, deprivation, and emigration. Working with the NEET youth population is one of the many challenges that Local Impact is focused on in Central Asia.

Local Impact, a partnership between the Aga Khan Foundation and the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), aims to address such complex challenges through a participatory design process. Local Impact was created as a joint initiative of the AKF and USAID to implement an innovative framework that puts local communities at the center of development for meaningful, sustained impact.

In this post, we share our methodology and reflections from the journey of addressing the challenge of NEET youth in the Kyrgyz Republic.

Transition from designing for communities to designing with communities

The human centered design (HCD) work under Local Impact is led by a team of AKF staff based in the country with coaching and support from members of our regional and global team. Adopting a co-design approach, we invited members from the local community who grew up in the region and have experience of working on youth initiatives to join our design team is Osh, Kyrgyz Republic: Gulzat Gazieva, a youth journalist; Asel Abdraimova, one of the founders of Youth of Osh; Dinara Chekirova, from Youth Public Foundation, and Linura Diushebaeva, a civil activist.

Embedding community members in the design team meant that our process was always grounded in youth experience. They not only provided invaluable perspectives to the team’s understanding of the challenge, but also had equal power to determine what ideas were selected, how they were designed, and how they were tested. They played a critical role in identifying community members who were open to engaging with us in this process by leveraging their personal relationships and trust with residents.

Engaging community members in the entire process, rather than specific one-off moments, builds a solid foundation to collaboratively tackle complex challenges as a community. The team also found this to be a unique opportunity to nurture a design thinking mindset and skills and develop HCD champions, especially in emerging developing context like the Kyrgyz Republic.

“In being a part of this team, I have learned so many new things that I am confident to bring to my work and organization. Some of the tools of human centered design methodology such as journey mapping and prototyping can be enlightening for those who are not used to seeing the human in the problem,” said Asel.

Understanding the human behind the problem: Who are the NEET youth?

When the team began working on this challenge, we were well-versed in the statistics, socio-demographic profiles, and the relevant policies, strategies and programs. However, we found the current understanding of the challenge from the lenses of employment, education or training to be one-dimensional, oversimplifying the real dynamics at play. Instead, we realized we needed to work bottom-up from the systemic nature of the challenge itself, through human experiences in all their complexity.

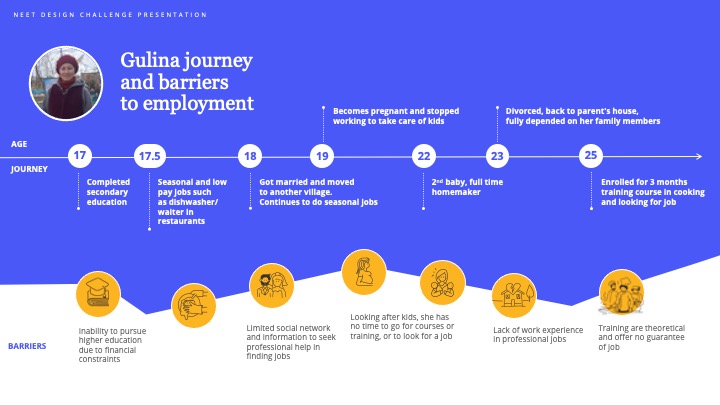

The team sought to conduct ethnographic interviews and observations with NEET youth to investigate young people’s experiences, the barriers and enablers they face in securing quality work, and gain a better understanding of their deeper motivations, values and beliefs. This also involved taking a life-course approach to understand youth transition to adulthood based on a series of transition events, including completion of initial schooling, leaving of education system, labor market entry, leaving the parental home, forming of family, and entering parenthood.

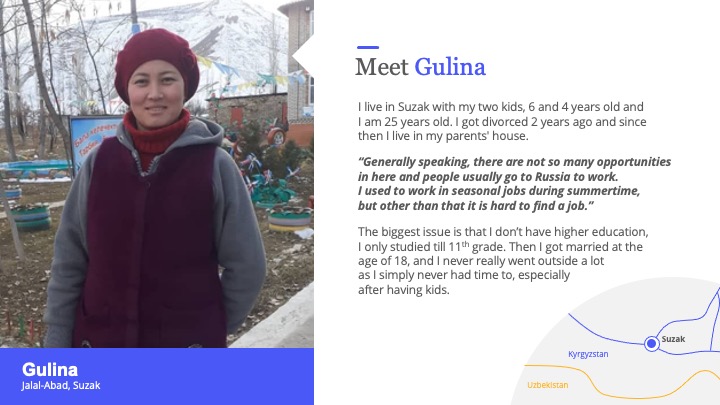

As we dug deeper, it became apparent that young people not in employment, education or training are a diverse group with varied pathways. The journey and challenges of a young girl, Husnida, who drops out of secondary school to support her conservative family, is starkly different from that of Gulina, a divorced mother of two young children who has never had formal work experience owing to early marriage and burden of housework. This led the team to develop four personas and journeys of youth who are representative of NEET youth in southern Kyrgyz Republic.

Each persona has a unique set of personal and professional needs and opportunity areas for effective intervention. However, in developing a strategy to reduce NEET rates, it is important to establish priority groups within the NEETs in the context.

Reframing the challenge: What do we mean by NEET youth challenge in the Kyrgyz Republic?

Our research showed that nearly all engaged youth had attended school, a training program, or held a job at some point in their lives. The duration of unemployment for young people was not very long, on average. Most unemployed youth (70.5%) found work in less than three months, and 28.3% were able to find work in less than a month. This implicates that NEET is a temporary status for most young men and women who are often in transition between education or training or employment opportunities.

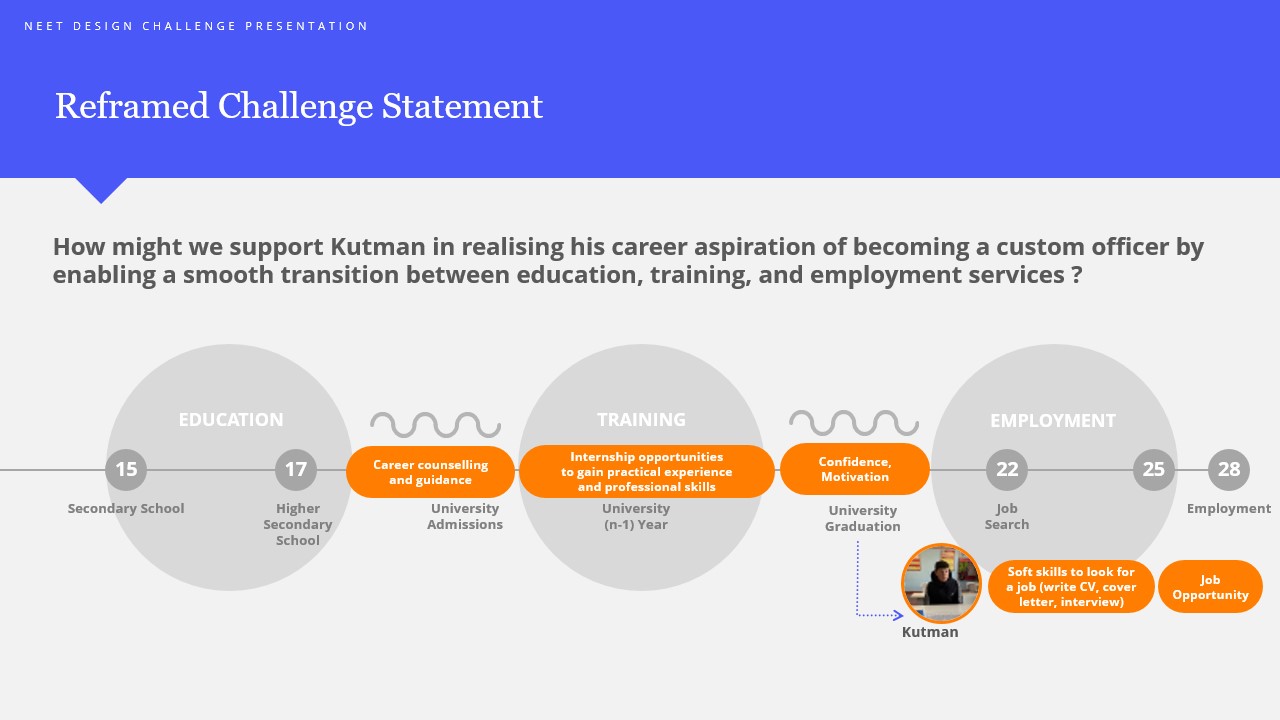

Another key insight that was instrumental in our understanding of the problem was that most young men and women had no idea of what they want to do in future. Growing up in small, isolated, mountainous communities with limited opportunities meant that most youth resort to emigration to earn a decent living. This has created a vacuum of professional community who can offer meaningful education guidance and career aspiration. The challenge is worsened by fragmented service delivery between education, training, and employment stakeholders. For instance, most universities and vocational training centers do not have employer agreements for student placements.

This line of inquiry allowed the team to reframe the understanding of the challenge from an earlier perception that was narrowly focused on skill acquisition as a pathway to better employment opportunity to a newer perception that is based on realizing a career aspiration by enabling a smooth transition between education, training, and employment services. Consequently, this allowed the team to develop an integrated digital platform that increases the quality of youth employment programming by providing supportive career guidance, immersive learning experiences, relevant market information, and accessible job linkages.

Towards Implementation: Co-financing, co-ownership, and product sustainability

When the team began iteratively testing the prototype with the stakeholders, we knew we were looking for more than feedback on the intervention itself. Our objectives were partly to secure positive stakeholder engagement in the process, improve stakeholder cooperation, and invite private stakeholder contribution through co-financing and co-ownership.

One of the key metrics of success for the team is to build a demand-driven sustainable business owned by a private stakeholder. While analyzing existing digital interventions, we found development partners who were trying to build similar product offerings as us. Rather than seeing them as competitors, we shared our idea, discussed potential for collaboration, and invited them to be a learning partner in our pilot. When we found a young entrepreneur with an existing Minimum Viable Product (MVP) of the solution, we shared our vision of the solution and invited him to financially invest in the development of the solution and take ownership of the business.

To promote intervention efficiencies, effectiveness, and sustainability beyond the project lifecycle, the team mapped synergies between the suggested digital platform and existing initiatives within the Aga Khan Development Network (AKDN). The team was successfully able to elicit buy-in from the Coalition of Employers, an initiative supported by Local Impact, that enables large employers to adopt new policies, practices, and programmes for the recruitment and retention of marginalized youth, especially young women. The other key partner was Accelerate Prosperity, an AKDN initiative in Central and South Asia that provides technical expertise, creative financing solutions, and market connections for small and growing businesses, also supported under Local Impact. In March, Accelerate Prosperity welcomed the young entrepreneur identified by our HCD team into its seven-week business acceleration cohort in Osh, alongside another entrepreneurial team working on a similar online recruitment platform. We anticipate one of these entrepreneurs, alongside our Coalition of Employers, to emerge as both willing and able to take forward the envisioned digital platform over the coming months. In parallel, the team is exploring alternative partnerships and pathways with other market system actors.

We are aware that for a challenge as complex as NEET youth unemployment, one intervention will never be enough to solve the problem. However, we believe this is a step in the right direction. The methods—human-centered design, systems thinking, strategic planning—augment one another and bring a unique value to a complex puzzle, as evidenced in this work. The intermediate outcomes of this work — co-design framework, personas and journeys, reframed challenge statement, and co-finance implementation strategy yield critical reflections to the way we design youth services, especially in geographically isolated communities.

I am grateful to my team, on whose behalf I author this article, for their unbending optimism and passion to drive this change. In the Kyrgyz Republic, I want to thank Dilya Dorgabekova, Mike Bowles, Indira Uzbekova and Sagyndyk Emilbek Uulu, as well as the Local Impact team, including Maksatbek Pataev, Tilek Abdiraimov, and Azizullah Baig for their guidance and collaboration on this project.

z z z