This blog is excerpted from a conversation with Abdul Malik, General Manager of the Aga Khan Rural Support Programme (AKRSP) in Pakistan. He recently visited Washington, DC, where he spoke at theWoodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, and with staff at the Aga Khan Foundation U.S.A. office.

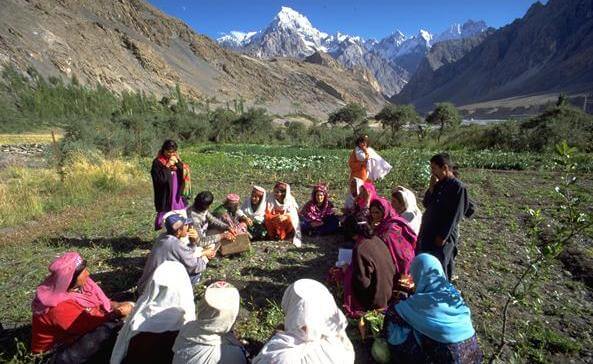

Village organizations are a central building block for participatory governance.

Q: What is AKRSP in Pakistan and how did it start?

Abdul Malik: AKRSP in Pakistan was started back in 1982 Gilgit-Baltistan and Chitral. These areas are very isolated geographically – very remote, extremely mountainous. They shared a lot of challenges – isolation, poor human capital, and poor agriculture– which created what one would call a spatial poverty trap: people were stuck in a mountainous area with meager resources, with very limited interaction with the rest of the world.

Our basic premise is that rural people have the potential to change their destiny, and that they want to change it. What mountain communities need is a trustworthy support organization that can help them organize and achieve their goals with human and financial capital. AKRSP was launched to play that catalytic role, and started with this basic approach – to form village organizationsas a key building block for participatory governance – and the goal of helping local people to double their income. It also aimed to create a replicable model of development for a wider world.

Q: Has that spatial poverty trap that you mention changed?

AM: To a large extent it has changed, in three main ways. First, in recent decades, government, AKRSP and others have invested a lot in building roads and other infrastructure. AKRSP has worked with communities to link up with secondary roads to increase their economic well-being. The second key change is in communication, especially mobile phones. Access to telephones back in 2001 was less than 10% in Gilgit-Baltistan and Chitral. By 2008, it was close to 50% and now it is believed to be even higher. The third change is an increasing trend toward decentralization of government. In 2009, Pakistan’s government approved an ordinance that gave more legislative power to assemblies in Gilgit-Baltistan. We still have a long way to go in seeing the fruits of this decentralization, but there will be opportunities for a convergence between what we are doing on the ground and what government is doing through decentralization. Through that, village organizations should gain better access to government services.

Q: How have rural livelihoods changed?

AM: Over the years, the sources of livelihoods in Gilgit-Baltistan and Chitral have diversified, with increasing amounts drawn from non-farm sources. More and more young, educated people are entering the labor market, but with very limited opportunities or skills. Our Youth Employment and Leadership Program recognizes this demographic shift and the need for private sector players in new sectors. Now, with higher productivity at the farm level, the question is, How do we add value to that production and link with sustained demand? Mountain Fruits Limited, which exports nuts and dried fruits to western markets, is one such response that is linking farmers to higher-value enterprises.

Men prepare apricots for drying.

Q: How do you choose products and opportunities in these areas where transportation is difficult?

AM: Yes, communication and transportation are major constraints. How do we find solutions that bypass them? Our decisions need to be driven by rigorous analysis and market information, so that whatever we do stands a chance for sustainability and growth. One example is dried apricots. We found that fresh apricots are not economically viable — they require much more transportation infrastructure and are perishable. But dried apricots are less expensive to transport and more durable.

The choice is also driven by larger social objectives. We want enterprises that address a large segment of the population. Apricots are produced by almost every household across Gilgit-Baltistan and Chitral, so it’s a very relevant sector for most households. AKRSP supported the initial research and development forMountain Fruits Limited. Once it became a viable enterprise, it was spun off to the private sector.

AKRSP has supported research and development in appropriate technologies to expand quality apricot production.

Q: How does AKRSP work with existing social structures to facilitate women’s activity in enterprises and decision-making for development?

AM: That’s a pertinent question: In places where local norms may not be open in terms of facilitating the mobility of women, how do you bring women to work in these enterprises? I think it’s a balancing act in which you want to be sensitive to local considerations but at the same time give women opportunities to expand their horizons. For example, our Mogh enterprise provides opportunities to young women in Chitral in the handicrafts sector by facilitating production and processing closer to homes and in women-friendly working environments.

Q: Looking ahead, what changes do you see taking place in themes that AKRSP addresses?

AM: Possibly three. In addition to building the capacity of civil-society institutions, we’d like to work with local governments to support capacity building for elected representatives. Now, elected representatives approach us about training in legislative and other issues. AKRSP cannot address this need alone but we can be one of the players.

Second, the role of the private sector is growing. When AKRSP started, the area where we worked was mostly a subsistence economy. Over time, the rural sector has grown and the private sector has to play a strong role. Government should work on creating enabling environment, and we can help link communities to private-sector entities.

Third, migration is taking place. What should our stance be? The fact is, there will be stronger trends toward migration that we cannot completely ignore. Perhaps we can find ways in which we (1) increase opportunities for income and employment locally, (2) help people who are migrating anyway to improve their odds of success; and (3) help people who move away stay connected, for example streamlining remittances and diaspora support. The idea of diaspora bonds is an interesting one to explore.